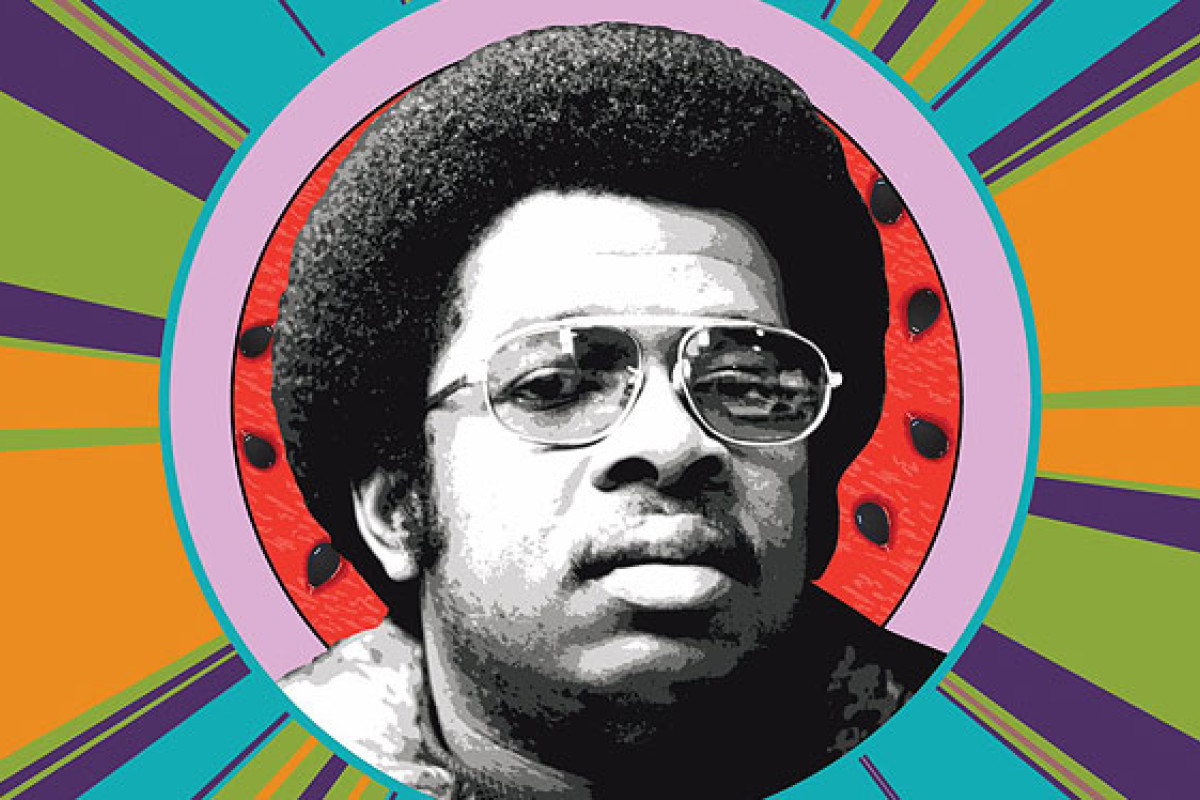

UNCUT FUNK interviews Fred Wesley

Nov 9, 1996

David Mills

A 1996 UNCUT FUNK interview with Fred Wesley that was republished on the now defunct New Funk Times website on August 23, 2003.

Trombonist and arranger Fred Wesley claimed his fame during the 1970s by adding a distinctive punch to the music of James Brown and P-Funk. In the '90s, he's got a whole new career as a jazz artist, recording in Europe and playing the hippest of small venues in the U.S.

After an October 1991 gig with Maceo Parker and Pee Wee Ellis at Blues Alley in Washington, D.C., Mr. Wesley was interviewed by Larry Alexander and Lorenzo Heard. They got the ball rolling by laying on him an LP titled "House Party," which had been due to come out in 1980 but never did, even though the "House Party" single reached the R&B charts.

In fact, until Fred Wesley's "House Party" was released on CD a couple of years ago by a German company, Lorenzo's copy was one of only 500 ever pressed. But in addition to being a rarity, this album has a special place in the artist's heart. In Part 1 of the interview, Fred tells the story behind "House Party," and talks about what it's like for him playing jazz clubs. In Part 2, he discusses the strong funk following in Europe, and recalls past colleagues among the Horny Horns and the J.B.'s.

LORENZO HEARD: Well Fred, the first thing I guess we should talk about is this "House Party" album.

FRED WESLEY: That was my baby, there. That was when I decided that I'm gonna do my own thing, write my own songs. It took me a year to write all these songs out.

HEARD: Basically what happened is that RSO never released this album, even though it's sitting before us right now.

WESLEY: And it has been sitting before us before. I've seen it other places around the world. What happened was, somehow -- I don't know exactly what happened. But Curtom, which was distributed at the time by RSO, they split. The same date that the album was set to release, they split, and the album just kind of got caught in the lurch.

HEARD: I'll tell you what's funny. I saw a review of this album back in '81. I read a review, got to work [at a record store], called a salesman, said "Look man, I read a review on this record. It's out. Where is it?" He kept telling me, "It has not been released, and I don't think it's going to be released."

WESLEY: I'm curious to know what the review said. Did they like it? Did they not like it?

HEARD: Well, the reviewer said it was a return to the down-home type feeling of black music, which I thought was a really good review.

WESLEY: Let me tell you what the idea behind this album was. The title song, "House Party," was inspired by the parties we used to have at my house in L.A. It seemed like every holiday a lot of people would show up -- sometimes it would be planned, sometimes it wouldn't be planned -- to bring food and liquor and their old ladies or whoever, whatever they liked. And the house was just open, everybody just had a ball. Sometimes it would go on a day, sometimes for days. And it was just a known thing, to go to Fred's house, we was gonna happen, right?

But in 1980, I had been through the James Brown thing, the Bootsy thing and the Count Basie thing, and I was back in L.A. doing just studio work, arranging and playing --

HEARD: Yeah, you were all over the place, man. You were arranging everybody's records. [Such as Curtis Mayfield, S.O.S. Band and Osiris.]

WESLEY: I was really busy at that time. But I wanted to really dig within myself to see what do I really want to do, what are my grooves, you know, and what kind of songs would I sing. This wasn't gonna be a vocal album, it just turned out to be a vocal album.

I started with the rhythm. I had all the tunes together, all different kinds of grooves, and actually the reviewer had it right. It was sort of down-home grooves, 'cause I'm from Alabama and these are some of the things that I grew up with. "I Make Music" was a funky kind of groove. "Life Is Wonderful" was a kind of a Latin groove that I was into. Even "House Party" was an offshoot of a Bootsy groove or a Parliament groove, and "Let's Go Dancing" was sort of a James Brown tune with changes. The tune "Are You Guilty?" was written by a friend of mine. It was the only tune that was written by somebody other than myself.

So all of these things I put together and I thought it was the perfect album. "If This Be a Dream" I thought was my attempt at doing a heavy song. I was so happy with it. I'm still happy with it. I still like this album.

HEARD: Great record.

WESLEY: But the thing that took my heart -- So many people in the industry were saying something like, "Fred, don't try to sing," "It's not funky enough," "These grooves are not hittin' in the marketing of disco."

HEARD: Plus you had the emergence of that crossover sound, which was exemplified by Michael Jackson and Prince.

WESLEY: And then it was starting to be into the synthesizer during that same time, so the industry demoralized me. This was my best effort, I was completely happy with it, and hardly anybody in the industry liked it. Everybody said, "Don't sing," "These are not the right grooves," "What does this mean?" They didn't get it, you know what I mean? Some of the songs are humorous. "I'm Still on the Loose" was supposed to have been a funny sort of a rap song. I thought these were wonderful! And everybody said "Ahh, nah." Only thing they liked was "House Party."

So I was like, "This is the best I can do, I love it, nobody likes it. Fuck it!" That was the attitude that I had. "I'm not gonna ever try this again. All right, next gig." I went back to Mr. Brown. I never again, until recently, tried to put another album together myself, and I've written very few songs since then.

Now I realize I should have stuck with it, because I figure maybe people told Prince and Stevie Wonder the same kind of a thing when they first tried to do it, because it was different.

LARRY ALEXANDER: From the stage, you have witnessed some of the most out-of-control, crazy crowds that anybody ever has. You've played with James Brown and Parliament-Funkadelic! After all of that excitement, how does it feel to be playing the small venues?

WESLEY: It's actually better because, like you said, those out-of-control situations, you know, there's so much aura, so much vibe connected with that, people come there crazy already. I mean, it ain't the music that do it to 'em, you know? These people done heard the records. Most of 'em come, number one, high (laughs), and then they come expecting to be crazy. So you really ain't got to do nothing but show up.

ALEXANDER: So now they're listening to you more.

WESLEY: Exactly. Now they come not really knowing what to expect. They expect to see three horn players without George, without James, without Bootsy, none of the flash, none of the glitter. In other words, what they expected to see was the background track. They come to see a track with no top on it. And then when we entertain them, most people are pleasantly surprised at the level of entertainment that they get. You see jazz people there that didn't know what we was doing, but they kind of enjoyed it. Then you got the funkers that come, and then we play jazz and they enjoy that.

ALEXANDER: Do you get the feeling that your musical contributions, especially with P-Funk, have been overshadowed by the glitter? That people don't notice what y'all did in the grooves?

WESLEY: They noticed it, but they never considered it as being an out-front element. They always knew it was there, because that's where our fame came from, being the ingredient in the funk, in the James Brown band. But we discovered that we could play maybe 20 James Brown songs, just the horn and rhythm parts, and people will enjoy it, not almost as much, *just* as much as if James was out there sweatin' and doing splits. It's the groove that get 'em. I've never seen James Brown get out there and try to sing without the band.

HEARD: I just want to let you know, your two Horny Horns albums on Atlantic are hot commodities in D.C.

WESLEY: And throughout the world. This is just a microcosm of what the world feels about what we're doing now. I had retired. I was in Denver, I had a jazz group, I'm learning tunes, I'm trying to get my jazz chops back together, 'cause I felt like that was what was left for me at this age, to go back to my jazz roots and try to be the best jazz trombone player that I could be. And I was doing pretty well at it.

But it was Maceo and Pee Wee that had spent some time in England. It was getting to them that tunes like "Four Play" off the Horny Horns album and "Pass the Peas" off the J.B.'s album, these were hit songs in the discos. They play these songs now and people will jump up like they did 20 years ago. I had to go get the album and play the tune, then I went, "Oh, I remember that tune." Because I was through with this! I was through with this!

ALEXANDER: That leads me to my next question. Europeans and the funk: What's up?

WESLEY: They got it! I mean, I'm not saying that they brought it back, but the Europeans made me aware of it. There was a few people in Denver, when I would play a gig, who'd say, "Are you the same Fred Wesley --?" And I said, "Yeah." 'Cause I'm playing totally different music, right? Bebop. I'm a be-bopper from way back. And then these people bring up stuff like this [funk] and that's all they wanna hear.

I put out a jazz album in England. I didn't care whether they made any connection, I just wanted the jazz to take hold on its own merit, you know, because I figured it was top-of-the-line jazz, too. But I'm telling you, I never could escape the funk.

It messed up my lip, you know. I can't play that hard stuff anymore. I'm saying, "Naw, Mace, I'm not gonna do that hard stuff no more. I got these real refined chops, I can play that *deedle-dee-dee-dee* and like that, now you want me to go *dat-dat-dat-dat* again! And stand on my feet and dance again?" I said, "Man, I'm past that. Call my son, maybe he'll wanna do that." (laughs)

HEARD: How did he convince you to get back out there?

WESLEY: It was the amount of money he offered me. (laughs) But still, my attitude was, go there for a few days, make the money, and come back and re-finance my second jazz album. I swear to God, that's what it was about. I never thought I would ever be back into it on this scale again. I never did.

HEARD: What say we get into a little history? The first thing I want to ask you about is Richard "Kush" Griffith.

WESLEY: Kush is one of the most creative people that I've ever known. And I've known some creative people, right? He's a great songwriter, he's a great arranger, aside from the fact, which you know, about him being an excellent trumpet player. He's a very good singer with a style of his own. What has happened to him, the reason he's not with us, Kush has diabetes. He has to go on a dialysis machine every other day, or something like that. And because of the diabetes, he's gone blind, so having him on the road with us is a big problem.

Sometimes he comes out and does sessions with us, when we're in one place where we can fly him in. He can't read music now, but he's got a quick ear, so he's still real good on sessions. We take care of him; when he needs something, we make sure he's got it.

ALEXANDER: What about Rick Gardner and Larry Hatcher?

WESLEY: Larry is a producer with Motown now. Larry was sort of a replacement trumpet player. You know, he'd come in sometimes and play with Parliament, but he never was a solid member of the Horny Horns. And of course Rick was the trumpet player throughout the Parliament days. We had wanted some high stuff, and Rick was just coming off a gig with a group called Chase -- used to play real flowery, scratchy trumpet stuff, real high, real fast --

HEARD: Couple records out for MCA.

WESLEY: Well anyway, I hadn't met Rick, but he's from the same home town as Melvin [Webb] was -- Kansas City. So [Webb's drummer] said try him, he turned out to be a very good trumpet player. Never could dance. (laughs) But could play! Very flashy, very dynamic. So he's our buddy too, and in the future I'm sure we're gonna use him sometime. But like I say with Larry, Rick never was from the beginning with us, you know.

ALEXANDER: What can you tell me about Dave Matthews, who was another one of James Brown's co-writers and arrangers?

WESLEY: Dave Matthews was an arranger in New York, good friend of mine, good mentor of mine. I learned a lot about arranging from him. Him and Pee Wee.

In early '69, Pee Wee left the band, and I inherited the bandleader job from Pee Wee, 'cause I was like Pee Wee's assistant. I used to copy music for him and just generally do little leg work for Pee Wee, so I was the natural choice to be bandleader when he left. And in my mind, I'm a no-nonsense type of person -- if I'm the bandleader, I'm the bandleader -- and James used to keep coming between me and the band. And I didn't like that at all, so I quit. I moved my family to L.A., and I started doing session work. I didn't do half as much as I thought I was gonna be doing.

During that time Maceo had formed his own group, All the King's Men, which consisted of most of James Brown's band. So James had to put together an entirely new band. He knew about Bootsy and knew he had a band, so that was James's band, essentially Bootsy's band, [but with] kind of a makeshift horn section. Dave Matthews came in and wrote all of the horn parts down, and what they used to do is go to a city, hire extra horns, like four trumpets, four trombones to play along with the rhythm section, just to pump up or augment the sound.

This went on for the whole year [of 1970]. And even afterwards Dave Matthews was still there doing the direction for the augmented band and the arranging for the albums. When I came back, James put me with Dave Matthews. I don't know why. I don't know if it was a racial thing, if he wanted a black guy to do his arranging or not, but I actually learned how to arrange and how to record from Dave, and that's when I got that job from him and I became the arranger on stuff like from '71 on up through '75.

HEARD: I notice you got a lot of co-writer's credit during that period. Exactly how much of those songs were you? Because I remember reading a Guitar Player article on Jimmy Nolen, and he stated that a lot of those tunes were jams that the band had already worked out, and James would come in and throw vocals on top. He said by rights, they know they should have gotten more writer's credit.

WESLEY: But it was kind of confusing sometimes. Some of them would be jams, some of them would be things instigated by James; he would hum stuff to me on the plane or in the dressing room, and I would write down the figures. Sometimes I would teach the band the figures he told me to write down, or I'd make up new figures in case I lost the paper. It got to be confusing who actually wrote what and how, what percentage of it was mine and what percentage of it was James and what percentage of it was the band.

But I'll tell you this: Whatever it was that came through my mind from James' mind to the band, the band always took it and made it into something. I mean, Jimmy Nolen had that style where you could give him a tune, he could play it with such feeling and soul that [it] became a classic guitar lick. Something like on "Cold Sweat," that was Pee Wee's idea, or maybe it was James's idea, I wasn't there, I don't know. But Jimmy Nolen played it. Now it's a Jimmy Nolen lick. So wherever the lick was instigated, the band -- Jimmy, Clyde [Stubblefield], Jabo [Starks], Charles Sherrell, Bernard [Odum], "Country" [Alphonso Kellum] -- all these guys made the lick into what it was because of the way they played it. So everybody deserves a lot of credit, more credit than they got. Like Jimmy Nolen should have gotten a piece of everything he ever touched. He should have been a very wealthy person.

Even "Cheese" [Hearlon Martin], a guitarist of limited skills who had a way of playing that dynamic stroke, which was actually Catfish's stroke, but Cheese had a way of playing it that made it jam. Like on "Make It Funky," all that stuff. It's the way you play it that makes it danceable, that makes it happen. So I imagine that anyone who ever recorded with James definitely deserves more credit than what they got.

Read more interviews.