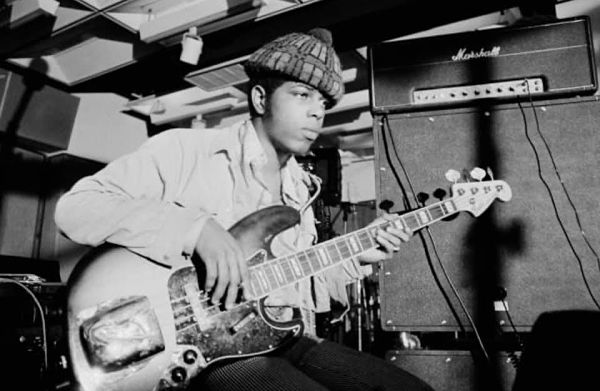

UNCUT FUNK interviews Billy "Bass" Nelson

Nov 9, 1996

David Mills

A 1996 UNCUT FUNK interview with Billy "Bass" Nelson that was republished on the now defunct New Funk Times website on August 23, 2003.

With Eddie Hazel and Tiki Fulwood dead, William "Billy Bass" Nelson is the last man standing of the original core of musicians that put Parliament-Funkadelic on the road to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Billy Bass left George Clinton's organization with some rancor back in 1971, but he has returned, travelling with the P-Funk All Stars the past few years. With some rancor.

When I interviewed Mr. Nelson in Washington, D.C., in August, it hadn't yet been announced that P-Funk was being inducted into the Rock Hall. Before that blessed announcement, Billy was caught up in the frustration of getting very little spotlight-time in the Mob's current tour, despite his status as a founding Funkadelic.

Part 1 of the interview centers on Billy Bass's recollections of the vibrant Plainfield, New Jersey music scene of his youth, and how he and Eddie came to be backing musicians for George Clinton and the Parliaments. In Part 2, he tells how Tiki joined them, leading ultimately to the birth of Funkadelic, and he makes a rather surprising declaration of his all-time favorite gig as a road musician.

DAVID MILLS: Take us back 30 years, when you and Eddie would get together at your house and just play. Did you know you were good?

BILLY BASS NELSON: At the time, being good or whatever, that didn't even count. We just wanted to play. When I first met Eddie, I was like 11, he was 12. Plainfield musicians used to get together from time to time in somebody's back yard, and somebody would set up a bunch of equipment. It might be two drummers, couple of bass players, and a bunch of guitar players. And they'd be jamming for all it was worth, playing all the popular songs that were out.

I met Eddie, they were playing one of them songs, "Wipeout." Guitar megalomania, you know what I'm saying? All the guitar players up there took a lead solo. When it came time for Eddie to take a solo, that motherfucker played some totally other shit. Everybody else tried to play like it was on the record. I knew then that he was good.

I was just trying to learn how to play guitar. I had neglected guitar pretty much all my life, 'cause my father plays guitar, and I wasn't that fond of my father. In any event, I couldn't avoid it any more -- I knew that I liked the instrument. I traded my trumpet for a guitar.

Eddie and I made a bond; he would teach me how to play the guitar, and I would teach him how to sing. So we just started getting together, he'd show me some chords, with acoustic guitars -- "Just keep playing that over and over" -- then he played something on top, and then we'd sing. We did that for a long time, man.

We got involved in a talent show at junior high school in the wintertime, and it was tragic, because I was so proud that me and him were gonna go do this talent show. Went to his house, picked him up, we cut across the Catholic school's parking lot, which was full of ice -- we were late -- and I slid on that ice. Now I'm carrying his guitar; my feet came up under me, and the guitar came flat down on the case. We never thought to look at it. When we got in the office at school to get our late cards, he opened up the case and the neck was busted. So we wound up not doing that talent show.

When we started working with George, it was like doing little guitar parts and making up little bass lines for the things that he was doing around the barbershop, which he would make tapes of and then take to Detroit on the weekends.

MILLS: Were you and Eddie familiar with, or impressed by, the stuff they were doing out there? How did you look upon George and these older guys?

BILLY BASS: Yeah, we looked up to 'em. Because that was our link to the real-deal shit. I mean, George was going to Detroit, that's where Motown was, and he knew all them people. So he was our direct link to that. From the gate, there was a level of seriousness about what we were doing. We always took it serious, never knowing what was gonna really happen with it. As far as going on the road and being out there on that level, I just never really thought about it at the time. We were doing local gigs, and *that* was amazing to me. My mother, or some adult in my family, would have to go to the clubs because I was underage -- this is like when I was 14 and 15 years old.

MILLS: With the Parliaments?

BILLY BASS: With the Parliaments, and another group called the Wonders, and Sammy Camel. Matter of fact, they used to do shows on different holidays. It may be Easter hootenany, just one for spring or summer in general, maybe one for the Fourth of July, Labor Day. Most holidays, it would be some kind of show in Plainfield dealing with all the local talent from New Brunswick, Elizabeth, Plainfield, Scotch Plains. It was always run by Sammy Campbell, and the Parliaments would always be either top billing or second billing to Sammy Campbell and his group -- that's the group Ray [Davis] came out of, the Del-Larks. There was another group called the Bel-Airs that Fuzzy [Haskins] was with. And Jo-Jo and the Admirations, that was the Boyce Brothers.

Richard [Boyce] and his brother Frankie, who played guitar -- Richard played bass -- would probably have wound up being the Parliaments' rhythm section. But what happened was, before the summer of '67, one of them got drafted, so the other two volunteered. They went in on the buddy plan, and Frankie got shipped out to Vietnam. And he got killed while he was over there. So that was the end of their group.

I had a little job working in the barbershop. But when I wasn't doing that, I was constantly playing the guitar -- whether to the jukebox, or if the Parliaments were practicing that evening, I would stick around, go find my little corner, figure out the guitar parts they was doing, and then play along with them.

MILLS: Guitar or bass?

BILLY BASS: Guitar. We couldn't find Eddie. By that time Eddie had gotten popular around the fast-life people and moved over to Newark, and was working with a producer, George Blackwell, who was I think [with] Carnival Records. That's where the Manhattans' first hits came out, on Carnival. I just couldn't find him.

So when it came time for us to go out on the road in '67 with "Testify," still couldn't find Eddie. I would've had Eddie playing then. But I went out on the road with 'em. And I discovered that I wasn't as good as I thought I was. Especially on the professional tip, and even George and them -- We got out there with some seasoned veterans like the O'Jays and the Temps. I mean, all the groups that we idolized coming through the barbershop, we wound up working with. And a lot of them in that summer, in '67. I saw more happen in that one year than I've seen in a lot of years afterwards.

MILLS: So what brought Eddie into the group?

BILLY BASS: We were on the road from May till August of '67, and when I just discovered that I couldn't play guitar on the level that it needed to be played, I knew that Eddie could. So we had about two weeks off, and I told George, "We need to get a rhythm section together, and the first thing I want to do is find Eddie Hazel." And I started in Plainfield with his mom, and she gave me some leads, and I finally wound up catching him in Newark. Found him, and talked him into coming over to George's house, which he did reluctantly. 'Cause I told him what the deal was, but he acted like he didn't want to have no part of it. He was already committed to working with George Blackwell.

MILLS: He was recording by that time already?

BILLY BASS: Yeah. So he came over to George [Clinton]'s house, and George talked to him and convinced him that everything would be all right if he'd at least give it a chance and check it out. You know, come on out there with us. So he hired a drummer from D.C. and a keyboard player from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and that was the first rhythm section.

After about three weeks, it just wasn't working. I knew it wasn't working, Eddie knew it wasn't working. George and them were satisfied -- "Oh man, give them people a chance." I said, "Nah man, it ain't about giving nobody a chance." In this situation, when you put something together, if it ain't right, you move on and you try to find the people that make it right immediately, because we ain't *got* time, you know? And we got confronted with, "Well it's *our* muhfuckin' group, who the fuck you think you are?"

As it turned out, my complaints about the drummer were totally legit, because we rehearsed, did a couple of gigs out there, and it just was weak. It just was not flowing right. So about the second week in September we played at the Uptown Theater in Philly, and that's where we met Tiki. He was the house drummer.

BILLY BASS: Tiki was the epitome of that show- time shit, with power. I don't think Tiki could really play soft, because he would break it down, and eight bars later it would be right back up again.

After about our first three or four days [at the Uptown], him and Eddie started hanging out. These mugs, after the show, they would disappear, wouldn't see 'em until the next day. One show, on a Sunday afternoon, man, we were supposed to be going on stage, and Eddie was not there. We were all the way up on the stage, curtains opening up, and here he come running out on the stage, where he had been out with Tiki all night -- doing what, I have no idea. They had two ugly bitches with 'em.

So I think it was that same day, that Sunday, after Tiki played, I pulled Eddie off, I said, "Man, what do you think about getting him to play?" And he said, "Man, I was thinking the same thing. This guy is bad." So we took it to George and them, and it was mixed. George was kind of open-minded about it, but other members of Parliament were saying how bad Stacy [the drummer] was, and he's gonna be all right.

They were gonna procrastinate on letting Tiki play so we could dig where he was coming from. 'Cause I had already deduced it down to that: The only way that they were really gonna know -- or for *us* to really know, too -- was to play with him. And Tiki said he knew the show, because everybody was watching us. I mean, our show wasn't as good as the Delfonics, but we were beginning to get a little professional edge on us.

Anyway, me and Eddie pulled Tiki off and said, "Look man, the only way we can pull this shit off is if, when we get up there and start playing, you just get on your drums, and wherever you feel like coming in, you just come in. Fuck Stacy." Sure enough, we were doing "Knock On Wood," the first song, and Tiki didn't even wait 16 bars before he came in, man. Where there was a turnaround -- a spot for the drummer to do a roll -- on that spot Tiki made his entrance and started playing. At first, the drummer didn't even notice because [Tiki] had blended in so well. Then, when he got tired of blending in, he stepped it up a notch. And the drummer just dropped his hands and turned around and saw Tiki cutting up like that, and right there on the spot started packing his drums up. And went home.

And the keyboard player that was playing with us, his wife was having a baby in Harrisburg, he just left us in Detroit, went home and he never came back. So that's where we went into that three-piece situation.

MILLS: You told a great story about the original Funkadelics going out as the backing band for Ruth Copeland, opening for Sly and Family Stone around 1971.

BILLY BASS: We were in Chicago at the amphitheater -- this joint is so damn big that they had us on one side, and this big steel curtain, and Evel Kneivel was on the other side, so you know how large it had to be.

That particular night, it was me, Tiki, Bernie [Worrell] and Eddie, backing up Ruth Copeland. She got three encores. The first two encores she filled, and the last encore *we* filled, and that was because on the second encore she introduced all of us as Funkadelic. Then, on the third encore, she let us cut loose. So when Sly came out on the stage, it was hot. It was burning up. Then he told Ruth later on that week, if not that same night, that she was going to have to find another band, or find another gig, that simple. So she started splitting us up. They couldn't find another bass player so I stayed. And Tiki stayed.

We as a unit, as Funkadelic, had officially left George, and we kept the name. We were still Funkadelic, but no longer with Parliament. And them fools didn't want to stick with it. We had John Daniels out there, he was gonna manage us. I worked for John ten years after Funkadelic, with a group he had called the Love Machine.

At the point that he made the offer was '71, and we were ringing like a bell from the first two [Funkadelic] albums. And [Daniels] offered exactly this: "I will make you guys rich, you'll all live here in L.A., you'll all have whatever you want, and you'll be famous all over the world." And he said, "All I want to do is make that happen for you." He said, "Naturally, I'll get mine. But you guys will all be millionaires in a couple of years."

MILLS: Sounds good. Made sense too.

BILLY BASS: And I told them that, man. And they went straight back to George. Eddie went running back to George. That shit hurt me, man, real real bad. Because I knew that that was our opportunity to do what *we* could have done, as individuals away from George. And it just slipped right on by.

MILLS: I've never heard of John Daniels. He was a manager, and you worked for him later?

BILLY BASS: When I was with the Love Machine, we toured from June of '79 until December of '79. And we toured Spain, Germany, Holland, England, Finland, Sweden, Norway, went back to Germany, and Switzerland. Man, if I can say that I really enjoyed being out on the road and travelling, it was with them.

MILLS: The Love Machine? What did they play?

BILLY BASS: Top 40. And dressed up -- they had Superwoman costumes, all kinds of little scanty stuff with their little beautiful bodies hanging out. That was their act. They had toured with Elvis Presley, Tom Jones. They did Vegas and all that kind of shit. They had record contracts throughout Europe. They were living very large. They very rarely worked in the United States, but every summer, we'd be gone, man. Blackbyrd [McKnight] did a couple of tours with us. We toured South Korea just before the Olympics, that was '87.

MILLS: And this was satisfying for you musically?

BILLY BASS: Oh I loved it, man. I loved it. It wasn't no stress. We couldn't even *make* no stress for ourselves. We got paid on time. It wasn't no phenomenal amount of pay, so once you accepted what you were gonna be making per week, as long as we got that, everything was fine. Just the fact of traveling all those different obscure places that otherwise we'd never have seen, and being around them fabulously fine women, man -- fine, *beautiful* black women. It was inspiration, seeing them shaking them booties on stage all night. And then the other part -- trying to get in it. (snickers) So we was busy all the time, man. And it was fun.

This situation here [with the P-Funk All Stars] has turned out to be a job. When it's a job, it's no fun. Of course, my job is doing what I like doing best, so in that light I should try not to complain about it and try to deal with it. But it's very difficult because there's a bunch of disrespect in this situation towards me, too. And George doesn't realize it, but he's one of the main perpetrators of that disrespect. And I told him about it, and he said it was stressing him out, me telling him about it. So I just stopped talking about it to him. But I'm serious. He has been disrespecting me.

He's had me back here, which that's great -- and I think that I'm supposed to be back here, I deserve to be back here. I'm one of the founding members of this. And he's told me that me holding on to my being an original Funkadelic is what's holding me back -- in this situation, and perhaps outside this situation.

I can't see it. I think that is one of the only things that I have in this world to be proud of, where I can make it respectable. Because Funkadelic is not known as one of the nicest groups to ever evolve, in terms of personality- wise and the lifestyle. No respectable parents want their children to grow up to be like a Funkadelic, if they can help it. We definitely ain't gonna be serving as no fucking role models.

But like I said, that's the only real legacy that I have. My claim to fame, you know, is Funkadelic. And for [George] to downplay it like that -- He just literally told me that me being an original Funkadelic don't mean jack-shit to him or nobody else. And that's wrong. That's wrong.

Read more interviews.